Noise

ISSUE NO. 04: HAYAL POZANTI

RITUALS OF SEEING

Words: 2487

Estimated reading time: 14M

Hayal Pozanti transforms nature’s signals into a personal language of shapes, colors, and meditative patterns

By Magnus Edensvard

Sometimes I wonder what inner sensations stirred the 17th-century Swedish botanist and explorer Carl von Linné and his disciples, as they identified countless new species of plants and animals across the continents they traversed. The work of artist Hayal Pozanti seems to echo that same sense of wonder—an attunement to the signals and mysteries of the natural world. Our surroundings can appear like a coded map, radiating impressions and cues that reveal themselves only to those who make themselves available, whose faculties are fine-tuned to receive—and, like Linné and Hayal, to translate and transmit.

Linnaeus (as he was better known) discovered so many previously unknown types of plant and animal life that it necessitated the invention of a new binomial naming system. He devised one using two-part Latin names (like Homo sapiens), which are still in use today. In a similar mode of generative discovery, Hayal seems to draw from a personal vocabulary, where titles such as Daylight Licked Into Shape appear as fragments possibly extracted from a longer text or poem.

Born in Istanbul in 1983, Hayal moved to the US as a child and later earned her MFA from Yale in the early 2010s. Her early geometric abstractions were rooted in a fascination with digital systems and technologies. Over time, however, her focus appears to have shifted—de-digitized, in a sense—toward a deeper engagement with the spirits found in pure nature. These days, technology seems less like a subject and more like a tool, helping her stay connected with those who follow her work and curiosities from afar.

After some years of living and working in New York and Los Angeles, Hayal and her husband decided to move to a small town in rural Vermont in 2021. As we caught up, themes of internal and geographic migration emerged—how time and place guide us more than we realize.

MAGNUS EDENSVARD: Did you celebrate Midsummer?

HAYAL POZANTI: Yeah. We have this beautiful flower garden at our house that’s in crazy full bloom, so we had some friends over this weekend. I picked flowers and made a little altar, like a crown, and put [out] water and candles. We wrote things that we want to let go of in the new year, and burned and put them in the water, like a little ritual.

Midsummer, like the equinox, is not something that I usually celebrate. There are other shamanistic, Turkish things that I celebrate around spring, but those are more for making wishes for the new year. Midsummer is when the sun is at its highest point. From now on, we’re going to get a little bit darker. From what I read, the ritual could be about what you want to let go of.

ME: You’ve relocated to Vermont, to this kind of paradise of spoiled nature—it’s almost impossible to imagine that you lived anywhere else. Can you tell me about how you seem to have found a new home there, and how your studio practice has readjusted since?

HP: While we were living in Los Angeles, I moved my studio to our yard. I’d been wanting to make a shift in my work for a while, but being face-to-face with the possibility of dying, the next day… It gave me the strength to let go of fear and embrace something a little bit more intuitive, a little bit more in dialogue with the natural environment. I had an outdoor studio for a year [in LA] while we were starting to go through the pandemic. Of course, in LA, we had our garden, we’d go on hikes, but [it was] still very much a big city. Here in Vermont, I live between mountains. The outdoors just became my whole world. I took on the practice of painting outdoors to making sketches outside, and then bringing them back into the studio. When something becomes part of your everyday environment, you begin to appreciate it, but it also seeps into who you are—into your soul. You become one with your surroundings. There’s an old saying: Whoever you surround yourself with is who you are.

ME: Indeed. I was going to ask you about the fractals or the personal lexicon of patterns and shapes you developed at Yale, and how they have been moving, shifting, renegotiating, and reshaping in your practice as you’ve moved.

HP: It’s essentially a language that I came up with and then taught myself. It’s visual, but it has phonemes; there are sounds to it. Each shape has a corresponding letter and number from the English alphabet. When you learn a new vocabulary, you bring that into whatever language you’re speaking. So when you’re bilingual or trilingual, your mind becomes this amalgamation of all the languages you know. As I transitioned into looking more at the natural world, I saw it in the shapes of the language I came up with.

I was also, at the time, reading about Hilma af Klint’s work, and that gave me permission to incorporate my spiritual interests into the work that I’m making. I was reading Ram Dass and Eckhart Tolle, and thinking about how to bring [meditation] into my studio practice. By invoking shapes or numbers through meditation, by being fully present in the moment, connecting with nature, and then translating that into a moment on the canvas. It’s kind of like being a vessel for energy. I’m sounding really out there right now, but the world is energy, and whatever energy you observe and put out into it. This can come to you in the form of shapes, numbers … being a translator for the natural world, and then putting that onto the canvas.

ME: With Hilma af Klint and other artists, colorists, and spiritualists, they used shapes and colors, often formulated into geometric, beautifully composed, balanced patterns. But if we look at your recent body of work, it seems that the organic shapes that you find in nature are your way of addressing that correspondence between the signals that may be received and the natural world that you see. What you put onto the canvas becomes a kind of offering, or a map. When you’re in the process of painting, what kind of mental state do you enter?

HP: Meditation really helps. When I go outside and sketch, I’m looking at something for an hour or two, which requires undivided attention and care. It’s very, very difficult to do that if you don’t have practice, especially in the world that we live in right now. To be able to sit still is a form of meditation called Zen meditation, where you don’t close your eyes. Sometimes I think about that when I’m trying to connect with the being that’s across from me—the life force in it, the life that it lives, its precarious position in the world—I try and give it as much care as I do, my friends, my husband, and the other human beings in my life. I look at it and think of it almost like I can talk to it—like it has something to say to me. Then, I come back into the studio. Usually, I listen to a lot of ambient music. It creates another kind of feeling, especially this type of ambient, classical, or more abstract music that gets you deeper and deeper into a state of trance.

ME: Whether it’s audible or visual, it seems you’re working with vibrations or patterns—notes that you translate. In order to get to a place where you’re creatively in tune, it’s really about the process. It’s about coming back to that same place again and again—to repeatedly be showing up for something regularly whilst not knowing what or where it is.

HP: So true. [Laughs]

ME: Then, when you get really good at it, it starts to come naturally. Between New York, LA, and Vermont, do you notice a change in how you show up to a day at the studio?

HP: Living in New York is a very intense experience; sometimes it just feels like you’re racing yourself for more. The moment you step outside, you’re like, Okay, I’m ready for the day. The city is here. You’re battling to get to the studio, and it’s go, go, go. There are so many people also doing studio visits who want to come by, and there’s more social activity. You’re constantly working, constantly socializing, constantly doing studio visits. Your work becomes like quote-unquote “work.” One of my professors at Yale, Chris Martin, used to say that the most important thing is to keep going to the studio, even if you don’t do anything, even if you [just] make some stupid mark. Just sitting there, looking at your paintings, and looking at your books. I write poetry, so sometimes I just sit and write. I love writing, even if I’m not physically working on a painting. It’s important. That part has never changed. Also, I think my work had a more digital, industrial feel when I was living [in New York]. I was interested in technology and what it was doing to us in our creative processes.

Moving to my studio in LA, I found a spot down the road from where we lived in Highland Park.I would walk there. I was the only person walking in Los Angeles. My husband was like, ‘Why are you walking?’ I was like, ‘Look at the street. It’s beautiful. It has flowers on it. Why isn’t anybody else walking?’ [Laughs] LA felt strange to me because of that.

ME: How do you relate to the advancements of technology today, like artificial intelligence?

HP: How I came to the paintings I’m making now is a pushback against what I thought would be coming to terms with generative art-making. Around 10 years ago, I had a show at the Aldrich Museum called Deep Learning. That’s when my fascination with artificial intelligence reached a peak. At the time, part of my practice was collecting numbers related to technological advancements, and I knew that artificial intelligence was going to be this huge leap in our lives.

Once I made that body of work, I wanted to push towards what I felt to be not artificial things, [things] that can’t be duplicated by artificial intelligence. What makes us humanly intelligent, as opposed to artificially intelligent? It’s things like our lived experience through our bodies, embodied cognition, because we perceive the world through our senses, through tactile touch. Painting with my fingers and hands became very important to me. So did paying attention to my dreams and following a more intuitive process of making. Human intelligence and the human mind are the amalgamation of a whole lifetime of experience. Your brain and my brain experience the world somewhat similarly, but also completely differently, because our neurological connections are unique. Your memories, your associations—there are universal aspects of being human, but also deeply individual ones that form and connect in ways that are inexplicable. Sometimes you wake up from a dream and you’re like, How the fuck did I even come up with that?

ME: Yeah, like most days. [Laughs]

HP: Things like that made me think we’re being faced with something, all of a sudden, where human intelligence isn’t so unique, important, or superior as we once thought it was. We’re also experiencing that through our relationship to other animals. Dolphins and whales can speak to one another. Mushrooms also have a kind of language that they’re communicating through. Trees are rhizomatic. I thought that what I needed to do, or what I wanted to do, was hold on to something that I felt was uniquely human, which is our embodied understanding of the world, our understanding of the world through memories, and also our relationship to the natural world. It’s uniquely human because we are organic beings. We need to eat. We need to breathe clean air. These are fundamentally biological things. We need other organic beings to be alive, and that relationship is not a relationship of just taking; it’s reciprocal.

I think the sheer energy we share with the natural world is what keeps all of us alive. We’re symbiotically connected. The organic spiral of the natural world creates a sense of common ease in the human eye’s interpretation when you’re looking at things that lack detail. When you live in a very minimal world, or when you live in a world that is full of just right angles and inorganic material, this causes stress in human bodies. That’s why there are now these offerings like forest bathing, or walking in the park, or touching grass. These are real ways human beings go back to being human. I want us to step back a bit and go back to existing in the real world. The digital world is very much real. You and I are having this conversation, and I’m grateful for that, but we can’t spend all our lives in here, in this box.

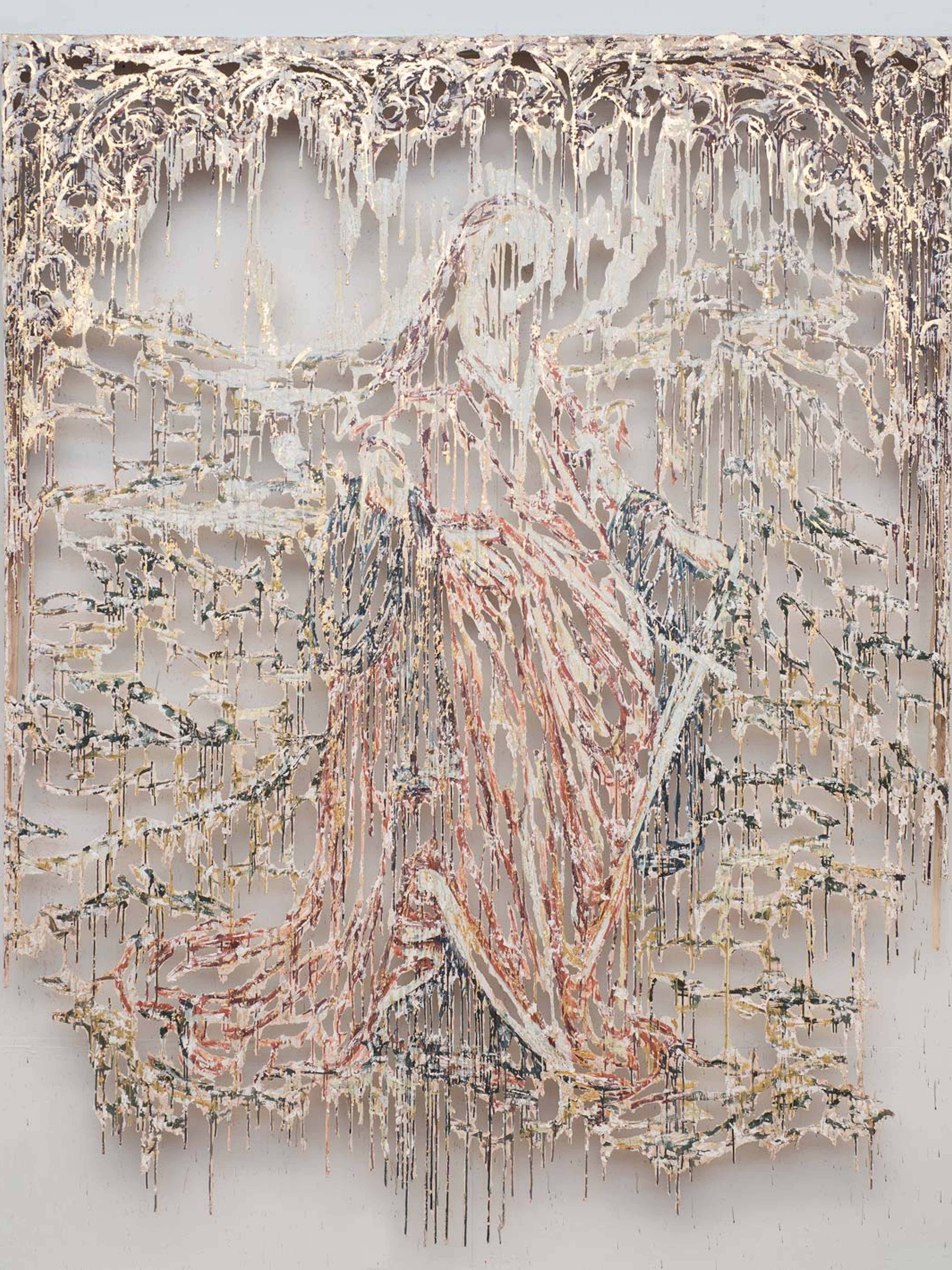

'Your Lips to the World,' 2025. Oil stick on linen, 80 x 120 inches / 203.2 x 304.8 cm © Hayal Pozanti.

"I think the sheer energy we share with the natural world is what keeps all of us alive."

'Thought I Heard You Whisper,' 2025. Oil stick on linen, 80 x 120 inches / 203.2 x 304.8 cm © Hayal Pozanti.

ARTS EDITOR-AT-LARGE

MAGNUS EDENSVARD

Artworks courtesy

the artist and Jessica Silverman

Beyond Noise 2026

ARTS EDITOR-AT-LARGE

MAGNUS EDENSVARD

Artworks courtesy

the artist and Jessica Silverman

Beyond Noise 2026