Noise

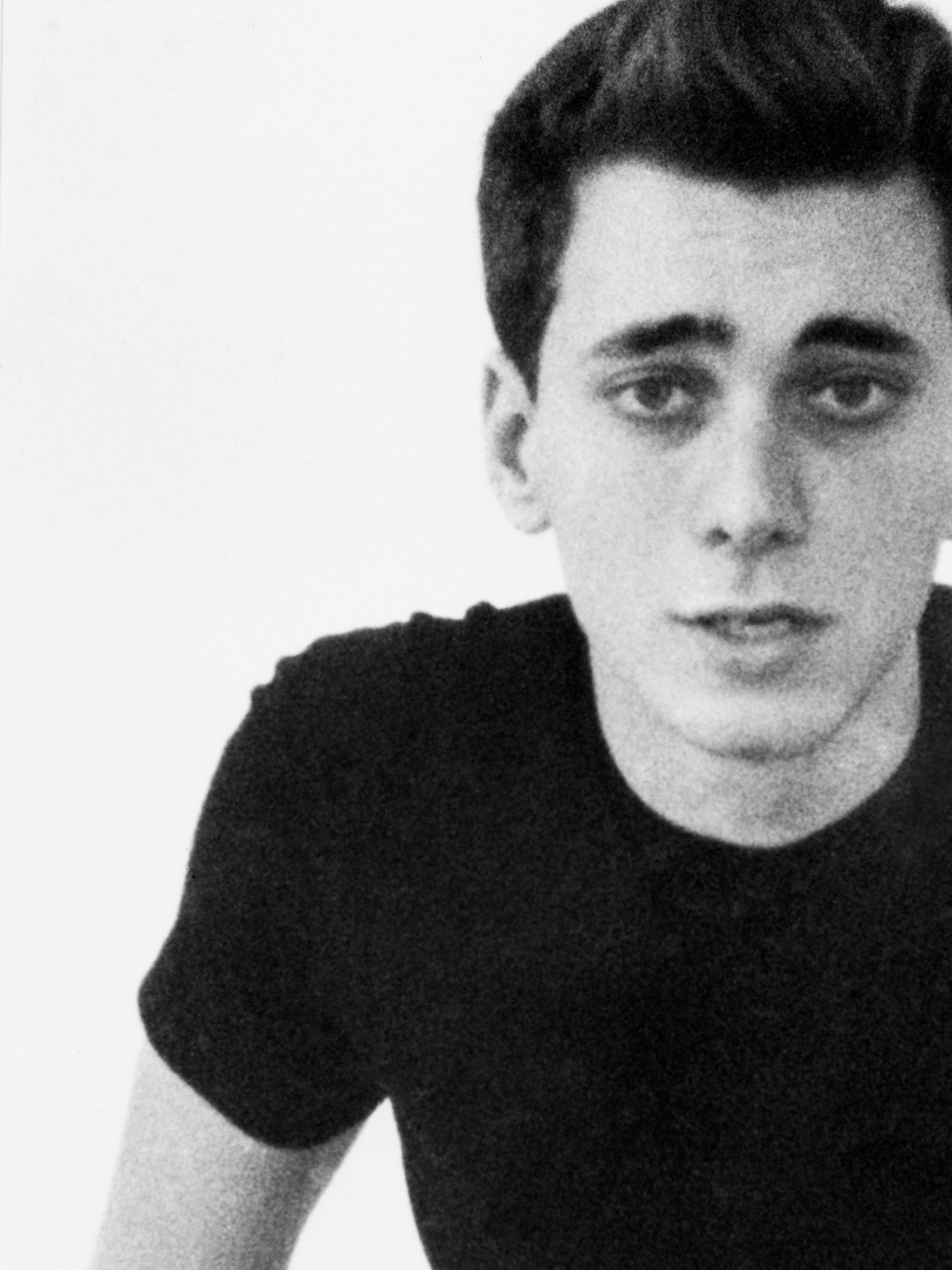

ISSUE NO. 04: SÉAN MCGIRR

“Maybe there’s no finite amount of pleasure. Maybe there isn’t a finite amount of pain. Maybe actually, we can all expand to our whims.”

MYTH AND MATTER

Words: 3151

Estimated reading time: 18M

Seán McGirr and Lauren Auder reframe rebellion as ritual, mining ancestral myths and queer desire to create new narratives

By Nicole DeMarco

In Irish folklore, trees are considered sacred. They contain medicinal properties—the flowers, leaves, and berries of Hawthorn support the heart and aid digestive ailments; the strawberry tree is a known antiseptic and can treat rheumatism—but they are also home to spirits, both ancestral and otherworldly. They are portals to the world of the fae, or Aos Sí, where fairies, nature spirits, and other magical creatures live. The sacred “Guardian Trees of Ireland” protect the five provinces: Eó Mugna (Oak tree), Bile Tortan (Ash), Eó Ruis (Yew), Craeb Daithí (Ash), Craeb Uisnig (Ash). As the days grow longer each autumn, they shed their leaves, only to see new growth come spring—symbolizing life and death, rebirth.

Seán McGirr grew up surrounded by nature, in the provincial suburb of Bayside on the outskirts of Dublin. It’s home to medieval ruins dating back to the 13th century and striking views of the Irish Sea. Though his family would often cross the Emerald Isle to the small, deep countryside village of Lahardane, where one of Seán’s uncles had a pub. It’s not hard to imagine the regulars going on about the stories of their people—rich Celtic myths of fearless warriors and forbidden loves—after far too many pints, as dawn lifts over shades of green. One such myth of the banshee, a female spirit whose mournful cry is often a signifier of death or impending doom, was evoked in Alexander McQueen’s seminal Fall/Winter 1994 collection, which Seán first discovered on Tumblr in his teenage bedroom. With his punkish sensibilities, he instantly felt a sense of kinship with the young rebel designer, Lee McQueen.

Now, many years later, heading the legendary fashion house—Seán was named Creative Director of McQueen after Sarah Burton’s departure in 2023, and his own stints at JW Anderson, Dries Van Noten, and Burberry—the banshee returned for Spring/Summer 2025, where a dark romanticism permeated the runway, twisted black chiffon thorns and silver chains trailing. “In the cycle of nature there is no such thing as victory or defeat,” the Brazilian novelist Paulo Coelho wrote. “<<There is only movement>>.” For Fall/Winter 2025, the McQueen myth met that of McGirr, who moved to London in his late teens and later attended Central Saint Martins, often finding himself in the London club scene. The collection was inspired by Charles Dickens’s Night Walks, about an insomniac who ends up strolling around the city until dawn.

Though we live in a time where the focus has shifted from art in fashion to that of the more commercially-viable, the well of inspiration runs deep. What Seán McGirr and Lauren Auder, a British-French musician known for making cinematic, orchestral pop—and perhaps Lee McQueen—have in common is a penchant for the gothic, the mysterious. As Lauren puts it: “from pre-Christian folklore to the modern myths of the 1980s and ’90s.” Both artists are master storytellers, mining their own myths to transmute identity across threads and synths. Just a few weeks shy of presenting Spring/Summer 2026 in Paris, Seán and Lauren spoke of folk horror films, fire healing, and the importance of provocation.

Lauren Auder: So, where are we going with this new collection?

Seán McGirr: It’s about pagan sexual liberation, pre-religion, old religion, and not subscribing to anything that feels modern-day, in a way. Pre-Stone Age. It’s very sexually charged. I think we’re missing a lot of sex in fashion now.

LA: Everyone’s always talking about the lack of sex in the Gen Z populace. I’m inclined to think that’s not true.

SM: Yeah, but then there’s a difference between having sex and projecting sex. From what I pick up on, people want to project sex more than ever.

LA: So, you’re looking at pre-Stone Age?

SM: Yeah, I’m really inspired by that film, The Wicker Man. Do you know it?

LA: I mean, it’s classic. Horror has made a huge comeback in the past few years, and I’ve been wondering what it means that folk horror is back in the fold. There is something very porous and incomprehensible about modern life, and I find the idea that there is some otherworldly force reassuring and comforting in comparison to the truly, unknowable forces of capitalism and machinery right now.

SM: I feel you. Have you ever been inspired by any of that ritualistic, folk horror? It’s a bit adjacent to nature and for me, quite animalistic.

LA: This is also what I’m touching upon. In a world where half the things around us work in ways that we don’t have any comprehension of, the idea of returning to something animalistic feels vital. When I was first starting in music, it was the kind of imagery that made me want to build worlds. I grew up in the South of France, in a small town called Albi, which has its own crazy history. There’s an agnostic sect there that was running the town, and was crushed by the Catholic Church. Probably, in a similar manner to what would have gone down in Ireland, where these community-nurtured belief systems were then raised in that light. That’s the underlying force that is often evoked in these folk horror pieces. The last collection I came to see, you were evoking banshees and Celtic mythology. Is it a celebration or a haunting?

SM: It’s more celebratory. It’s not spooky or haunting. It’s maybe a bit disturbing, but there is a weird kind of authority about it as well. Woman as an authoritarian, or something. That woman was a bit angry and a bit romantic, the banshee. Now, I think it’s more about this shamelessness. She’s a very complex woman, the McQueen woman. She’s quite layered.

LA: When I think about all this and the Bacchanalia, to give up one’s identity to this party, or these kinds of things, feels really prescient. [One of] the first press pieces about the McQueen shows mentions the Theatre of Cruelty. This idea of new cinema, new theater, and giving oneself up to channel this spirit of hedonism.

SM: Don’t you have music coming out soon?

LA: I have music coming out next year. I wanted it to feel like a lot of raw emotion, sexuality, and freedom. The first record was very inward-facing and dark, and about processing things for myself. This one is about how one wants to be in the world. The first chorus on the first song of this new album is “let greed in”...

SM: Let greed in to sort of protect yourself?

LA: I think as queer people, the idea of desiring more, it feels like there’s a blockade—they can’t even access that desire. It feels like a radical thing to be greedy in that way, and that can change the whole outlook. Maybe there’s no finite amount of pleasure. Maybe there isn’t a finite amount of pain. Maybe actually, we can all expand to our whims and whatever. It’s rebellious, because that’s not a position that you’re told you can take.

SM: Yeah, I know what you mean. It’s funny when you want to rebel against something, but you can’t really control it. It just comes naturally, because it’s such a visceral feeling.

LA: Do you feel like that’s a big motivation in your work?

SM: It’s not to rebel against, but to sort of provoke something? I mean, it’s the reason I do anything. I love this idea of creating something, not necessarily to provoke, but to create something that you’re really obsessed with. You know, when you get obsessed with a leather jacket or a piece of insane jewelry or a shoe, and you’re like, <<Oh my gosh.>> I don’t like this idea of doing something just to provoke a reaction, but to do something that you want to become obsessed with. When I do a show, I live with it for the following six months. I go over mistakes, or I’m like, <<Ah, this could have been better.>> It’s hard to live with it, right? Like, it’s just part of your soul.

LA: The best way that I’ve been able to live with the idea that this work is going to be there forever, is to think about myself in life terms. The final piece is the whole. I think so much of creative output, in general, is being devalued. Trends go so fast because of the internet. But the real key is not actually the thing in and of itself, it’s the continuation of it—how it’s evolving and what it relates to in your life.

SM: The best is when you have some kind of flow. I do a lot of psychoanalysis. It helps me with a steady creative flow. It’s easy to be blocked, but because I confront what I’m working on every week, it helps me stay within the weird rhythm.

LA: Self-interrogating is a necessity. That’s going to be the driving force of any creative pursuit.

SM: It’s great because your work feels so personal to you, and that’s why people connect to it.

LA: I was always drawn when I was younger to emo music, the rawness of those things feels like a safe place to explore in music. Do you feel like music is a driving factor in your work, and does it inspire you?

SM: It definitely gives me energy. I’m similar, but I missed the emo thing. I was really into Marilyn Manson and Nine Inch Nails. Still really into Nine Inch Nails. I loved that harder, intense, almost danceable metal. I play a lot of that in the studio, but I grew up listening to [it]. I went to that Deftones gig in Crystal Palace in June, and there were like 50,000 people. It was sold out, all over TikTok, <<crazy>>. I didn’t realize they had such a huge following.

LA: I’ve never had a TikTok, so I always get surprised when that’s happening, and it must feel the same way for these bands. That’s the amazing thing about having such access and that makes me feel very positive about the internet: the archive of everything.

SM: That’s a good point. For so long I’ve been offline, and it’s only in the last month or so that I started going back on Instagram. Sometimes it’s just good to go to the party, and sometimes it’s good to leave. And then you go back, and then you leave.

LA: What made you want to go back into the party?

SM: I was just curious and missed connecting with people. I was sitting next to Kim Kardashian at the Met Gala last year, and she was like, “Oh, I have to go. But what’s your Instagram?” And I was like, shit I should be on Instagram. It’s superficial and dumb, but at the same time this archive of the internet is a really interesting thing, and that’s something to be protected and inspired by.

LA: It’s harder now, because the internet is driven by algorithms. But because I was so isolated [growing up], the internet felt like everything to me. Some of my earliest memories of having an interest in fashion was through finding McQueen archives on Tumblr.

SM: I was the same. I grew up in Dublin, which is a capital city, but it’s still kind of provincial. I remember seeing McQueen shows on YouTube in the mid ’00s, and being like, what is this? McQueen, Comme des Garçons, Westwood. That was a little irreverent, or slightly punk, so I was really into it. I was a difficult teenager, I think. So, I was drawn to these kinds of fashions. This is a complete segway, but do you read much?

LA: I have always been an avid reader. That feels like a key part of my creative process, just reading and consuming books.

SM: I read quite a lot this summer. I was reading Sally Mann’s memoir. I love her photography, it’s just my favorite. She has kind of a wild upbringing and she’s very controversial in America, because she took nude pictures of children, which are just so insanely beautiful. I guess they came out during the post-Ronald Reagan years, and what they call Satanic Panic. She was sort of the scapegoat for a lot of people’s problems, but it’s a really interesting book. And then there was this Gore Vidal book, The City and the Pillar.

LA: Do you feel like any of this has been inspiring where you’re going creatively?

SM: I mean, you know how it is, you’re just inspired by everything, you soak up things and then put them back out into the universe. It’s just being wrung out and then soaked up again.

LA: I live in London, as do you, and it’s really good for being inspired, so I do a lot of the writing here. But when it needs to take form and take shape, I always find it easier to get out of my routine. Was that why you left for Mexico?

SM: It was a holiday, but it was also a bit of an excursion. I did fire cleanses, which were amazing. My friend introduced me to a shaman who massages you, and when they get to a part of your body where they feel tension slash negative energy, she absorbs it and then burps it out. She was in her mid-60s, Mexican, spoke no English, just burping away. I also saw a fire cleanse person, kind of more religious, and that’s when you go to them with something in mind. You write it down on paper, you write down the people involved, and she reads it in front of you and asks questions. Then she puts a ring of alcohol around you, and lights it on fire. Then you step out of the ring, she puts the piece of paper in the middle of the ring, lights it on fire, and says a lot of things in Spanish, which I do not speak, so I wasn’t aware of what she said.

LA: Do you feel like it worked?

SM: Yeah. [Laughs] I do. I also did pretty hardcore Temazcal sessions, where you sit in a super hot room with all these plants, and someone’s hitting you with leaves and sage and lavender. It’s really, really, hot, kind of unbearable, but you have to purge. It’s about breathing. Then you do ice baths. I did things for my body, kind of reset it a bit, because you store so much in your body.

LA: They say it keeps the score.

SM: Totally. You want to feel like you see things with fresh eyes, and you want to inspire yourself on a daily basis. I think it’s good to do things like this, for me anyway. The museums are amazing as well. The anthropological museum in Mexico City [has] all these sculptures from hundreds of years ago—a lot of death references, skull references, but gorgeous—like it doesn’t feel heavy, or sad.

LA: Death was a part of everyone’s life, but it feels so disentangled from contemporary living. It’s so sanitized. Even sex, everything seems to be somewhat hidden away, and unaddressed.

SM: And not confronted. That’s the point of analysis, is to confront.

LA: That feels key to Alexander McQueen as a brand, these memento moris constantly there. You made the T-Bar such a thing, which reminds me of Victorian stopwatches.

SM: Yeah, he used that as a detail in the ’90s. I’m always thinking about past references, but it’s more about feeling an energy in the air now, I guess, isn’t it? Everything we do is instinctual, and you just have to do it because that’s how you feel about it. That’s what it needs to be.

LA: It’s interesting, because you’re working seasonally, so there’s already delineated timelines.

SM: As long as I have enough time, I work pretty well with deadlines. I usually finish a collection, and then two days later, I will start on the next one because I already know what the next show is going to be about, even though I haven’t done any research yet. When it’s flowing, it’s flowing. But deadlines are great because, in the end, it’s a business. You need the fabric suppliers to be able to do their job on time, then it needs to be made, and it needs to go to the stores at the right time.

LA: The understood narrative is that the commercial side of these things is always inhibiting the creative process, but that can also lead the process.

SM: Commercial is not a dirty word. When you balance everything, it’s quite magical, actually. Maybe you can create something that feels quite modern. The dream is to create work that has a cultural relevance to it. Not just in your own little industry. [Work that’s] in a subversive, subtle way, putting a mirror up to what we’re living in.

“I think we’re missing sex in fashion now.”

PHOTOGRAPHY

THEO SION

Beyond Noise 2026

PHOTOGRAPHY

THEO SION

Beyond Noise 2026