Noise

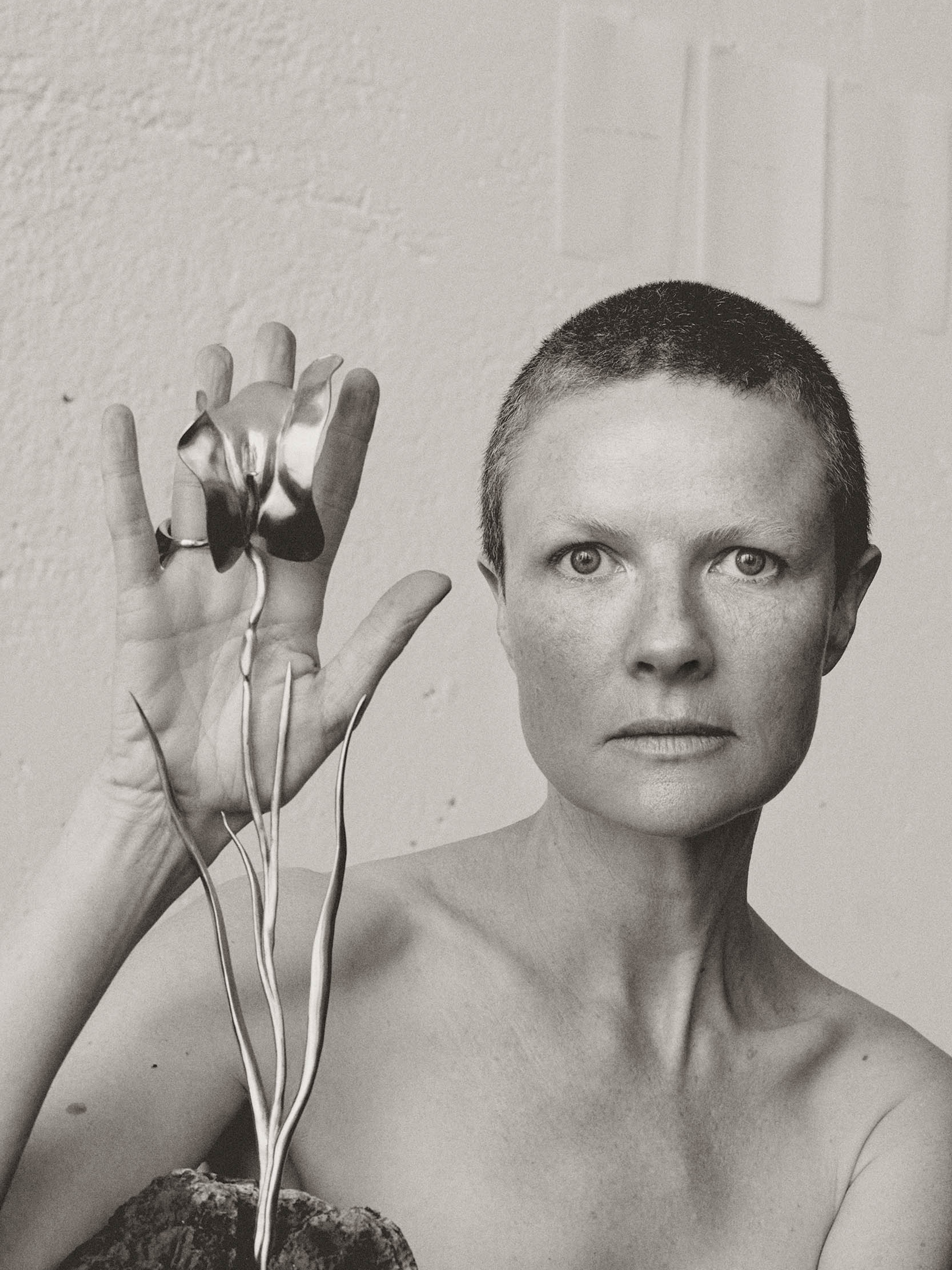

ISSUE NO. 04: ISABELLE ALBUQUERQUE & LOUISE BOURGEOIS

ARTWORK BY ISABELLE ALBUQUERQUE & LOUISE BOURGEOIS

FERAL BLOOM

Words: 2564

Estimated reading time: 14M

Isabelle Albuquerque and Louise Bourgeois’s creative kinship collapses time. In a new exhibition curated by Libby Werbel, each artist’s work ignites the other’s presence.

By Magnus Edensvard

Nowhere does the notion of creative expression through collaboration resonate more profoundly than in the work of Isabelle Albuquerque. While her art unfolds across series, it is always underpinned by dialogues and collaborations that are at once material and metaphysical. She engages in lucid relationships with foundry metallurgists, perfumers, lichens, and flower ovaries alike. Isabelle has developed an acute ability to communicate and exchange information across what she refers to as a feral timeline—drawing from both past and, at times, future sources. Such correspondence happens, at the best of times, with legendary and pioneering artists and writers such as Noah Davis and Ursula K. Le Guin, who once spearheaded their creative ideas in their time.

Another such remarkable collaboration will be showcased in The Wandering Womb, an upcoming two-person exhibition featuring a new body of work by Isabelle Albuquerque, presented alongside sculptures and works on paper by Louise Bourgeois at the lumber room in Portland, Oregon, spearheaded by its director and chief curator, Libby Werbel.

Isabelle and Libby have conceived an extraordinary engagement that encompasses the entire space. This will include a new scent-based piece by Isabelle, subtly influencing the visitors’ senses as they encounter her works carefully interspersed with those of Bourgeois, most of which are drawn from the Miller Meigs Collection housed at the lumber room.

Ahead of the opening of The Wandering Womb, Isabelle and Libby opened up about their evolving creative and curatorial exchange.

ISABELLE ALBUQUERQUE: You first came to my studio when I was still in MacArthur Park across the street from our mutual friend Math Bass’s studio. It was during the time when I had installed a stripper pole in the middle of the space and was imagining it as a tree trunk. In those days, I was dancing with the pole—I loved the smooth steel! I was also trying to understand how to connect apple branches to it to make it into a kind of symbolic tree of knowledge. At that time, I was obsessed with these paintings of the Garden of Eden where the devil appears from behind the apple tree as a feminine serpent—her face mirroring Eve’s. I remember we talked and talked, and when you left, you gave me this small, beautiful piece of lava. I still have it. Remind me where the lava came from?

LIBBY WERBEL: It came from a volcanic island called Lanzarote, in the Canary Islands. It was the home of this architect named Cesar Manrique, who I am obsessed with. That lava rock plays a significant role in his work. The day we met, I was actually operating at a pretty high frequency because I was leaving LA the next day, after having spent six months there working on an exhibition with Math. But I knew I had to meet you before I left, so we squeezed in a studio visit in the final hours. I had the lava with me to help keep me grounded, just in my pocket. We had such an incredible conversation about the Garden, the idea of the original sin, futurist feminist ideology, and most of all materiality. Time melted away. When I left, I felt so much calmer and realized it wasn’t the stone that had helped make that happen; it was you. So, I didn’t need it anymore. It was a fateful day.

IA: It really was. And now we have hunks of lava in every corner of our exhibition, grounding the exhibition itself.

LW: This lava has lichen on it though, which is important. Can you explain how the lichen factors into our thinking?

IA: I just love how the lichen exists in this in-between-simultaneous state. Lichen is not a plant or an animal. It's a symbiotic relationship between a fungus and a photosynthetic partner, usually a green alga. And they can live entwined as one together for thousands of years. It felt right to have this kind of eternal symbiosis, especially when making a two-person show. Working with the works of Louise Bourgious gets to be a kind of conversation across time. I feel incredibly moved to be in this conversation with Louise … and with you.

LW: Yeah, me too. I was remarking the other day on how prolific and definitive LB was in her sculpting. There was so much certainty in her objects. Especially when writing or speaking about them. She was just this force, a conduit, plowing through time, pouring sculpture directly out of her unconscious. Very clear on what she was making and why. But maybe she wasn’t allowed to be uncertain, exactly, based on the time period she was making her work?

IA: Or her not-knowing had to be a little more masked. Or maybe that was the unconscious for her—a place of not-knowing. I think she saw her work, especially the sculpture as a kind of exorcism, and I really relate to that. They come through you, sometimes in an almost brute force kind of way.

LW: I read one of your interviews where you said you like to make work that exists outside of a conventional timeline, and I think Louise did that as well.

IA: It’s true. Especially in the Orgy For Ten People In One Body sculptures. I see that series as existing on a kind of feral timeline where women have always had full agency of their bodies and their own pleasure. I imagined a history of sculpture where the nude was not about a gaze that looked onto the body, but instead a gaze that looked out of the body. An object that resisted its own objectness. A body that was being looked at and looking at you at the same time.

In my new body of work, Alien Spring, I find myself more often looking forward in time. A more speculative kind of looking. Perhaps that is why writers like Ursula K. Le Guin keep appearing in our conversations around the show.

LW: I find myself very drawn to artists who are rethinking or reworking history and writing it anew with their art. People who are reframing the past, present, or future. That’s a patterned language that keeps showing up in many of my exhibitions, and it’s clearly here with you and Louise’s work. I am also always thinking about the container itself. For you and Lousie, the body is the container we are focusing on. The container being the thing that holds the idea, that holds the picture, that holds the feeling. The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction by Ursula K. Le Guin has actually influenced a lot of my creative thinking about curating. I know we both made it to that Venice Biennale the year Cecilia Alemani curated? She actually, much to my delight, references that story beautifully by titling a section of the exhibit: A leaf a gourd a shell a net a bag a sling a sack a bottle a pot a box a container. And that’s just it: Le Guin proposes that the container was the original “object” or invention that propelled human evolution forward—not the weapon—as in the stories told or passed down by men. The neanderthal smashing a skull with a log. No. We survived because we figured out how to hold on to something and move with it.

IA: Yes. Bodies also are holders of new life, intelligence, and information.

LW: Right? Which also means the womb. That’s the first true container! We chose the phrase “the wandering womb” as our title, in reference to an old medical theory going back to Ancient Greece that proposed that women suffering from hysteria or other ‘unpleasant’ behaviors had a uterus moving through their body. It was even called an “animal moving within an animal.” So we are pointing to history’s proclivity to align the womb with a woman’s power, and what makes her a threat. That in and of itself is a perfectly rich starting point for thinking about you and LB’s works in dialogue for this show. But I also really want to think beyond the womb as an organ, but more as this fertile, creative center point.

IA: Yes. The womb is such a connective place, too—it is a place of becoming. It can gestate a child, of course, but also an idea or a sculpture or a building or a dream. Sometimes, I think about the act of making art as becoming pregnant with nothing. This is my favorite state in the studio. I am also fascinated by microchimerism—a phenomenon where the fetal cells of a baby stay in the mother long after the baby is born, sometimes changing her body in significant ways. And also the idea that when you were a fetus in your mother’s womb, and your mother was a fetus in your grandmother’s womb, the eggs that would later form you were inside your grandmother’s ovaries. This state of multiplicity guides my work in a deep way.

LW: By making these sculptures in these lasting metal materials, as actual 3D prints of your body, it’s also a continuation of your mitochondrial strand or your cellular makeup living on. This version, the sculpture of your form, will probably outlive generations of your family.

IA: Yes. They really are my offspring. And I like imagining them in a future where humans have changed significantly, and they become almost a memory or reminder of the kind of corporeal experience humans have now, but that is changing rapidly.

LW: Tell me more about your thinking on the work’s response to AI.

IA: I think of it more as alien intelligence than artificial intelligence. We have so much to learn from other ways of thinking. Algorithmic ways of thinking, but also the thinking of animals and plants and gravity and dirt. I have been thinking about flowers so much lately. Trying to learn from them. The way they shift between multiple genders and have interspecies intercourse. The way the face of a flower is the unconscious fantasy of a bee. These alien intelligences are all around us, and we have so much to teach us about the ways we might evolve.

LW: I like how you are playing with this intersection of nature as an eventuality in the conversation around technology. And in some way, this evolutionary potential of this alien intelligence to help us—

IA: —to integrate new ways of being. The flowers I am making now are a hybrid between human and flower forms. To be in a conversation with flowers is to be in conversation with light. It’s like they are teaching me a more heliotropic way of being.

LW: I can see that. I wonder how you see the <<Meadow>> series expanding on your previous work about the body? And how do you see it in conversation with Louise’s work?

IA: Flowers are a metaphor for desire. It’s interesting because Louise grew up in a tapestry family in France. Her father would bring home these large rugs with nude bodies on them, and as a child, it was Louise’s role to take out the genitals and sew flowers on top of them. A flower is never just a flower. Ha!

I started thinking about the flowers when the last fires were burning over my studio. Every time I slept, I dreamed of miles and miles of wildflowers growing in the ash, which they actually have. The flowers in our show and in Alien Spring are the flowers that came after the fire. I like the promiscuousness of a flower’s life. When a bee and an orchid engage in cross-species pollination, the blossom is the receiver, but it’s communicating so much: its color, the way it feels, the scent, every single part of it is bringing that bee to its pollen. The power of the submissive. The flower is transforming herself in response to the desire of the bee. And this feels connected to questions that I think a lot of people are asking right now: How do we change ourselves to meet another intelligence? We’re all doing that now with AI, whether we’re kind of conscious of it or not. Flowers have been communicating across species and intelligences forever. How do you encounter another intelligence, and how do you communicate with it if it speaks a different language?

This is why I am happy we are developing a scent for our show; it’s a different way of sharing information, too, of communicating nonverbally, but still a very embodied communication.

LW: When we first started talking about the flower sculptures, we were talking a lot about gestation, and regeneration—which is what you were experiencing in real time as you watched things grow after a fire. You sent me the best note, “You smell the exhibition before you see the exhibition. Burnt cedar, burning wax, fresh dirt, flowers, the sculptures lay on burnt wood. Piles of books from my library, rugs, dirt… time is different here.” Much of your work and LB’s work is about the sensorial, and memory. Bringing in smell became an opportunity for us to marry the work and create something visceral. To incite memory. We want to make you feel this show in your body.

IA: Yes, exactly. I’m always shocked when I encounter an LB work—the way it unlocks something in my body. It’s as if she is communicating directly with my cells.

“How do you encounter another intelligence, and how do you communicate with it if it speaks a different language?”

ARTS EDITOR-AT-LARGE

MAGNUS EDENSVARD

Photography

Isabelle Albuquerque

DESIGN

Jon Ray

Beyond Noise 2026

ARTS EDITOR-AT-LARGE

MAGNUS EDENSVARD

Photography

Isabelle Albuquerque

DESIGN

Jon Ray

Beyond Noise 2026