Noise

ISSUE NO. 02: MODERN ART

FIVE ARTISTS USHERING IN THE NEXT GENERATION OF CREATIVITY

ASTRA HUIMENG WANG BY KOBE WAGSTAFF

'To Have Still the Things You Had Before (After the Stravinsky’s Soldier’s Tale)' 2021

Hand-flocked baby grand piano with 400 bullet holes

170 x 147 x 160 cm

Image courtesy of Astra Huimeng Wang

MODERN ART

Words: 741

Estimated reading time: 4M

By Magnus Edensvard

Astra Huimeng Wang (b. 1990, Hohhot, Inner Mongolia, China) embodies an art practice that, according to her representing gallery’s profile, incorporates the creation of events and circumstances, as well as studies on the manufacturing of truth and identities. Astra has collaborated extensively with orchestras, poets, actors, and even strangers. With an MFA in studio art from the San Francisco Art Institute and a BE in biomedical engineering from Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Wang is currently preparing for her second solo show at Make Room Gallery in Los Angeles, set to open in January 2025. We jump into the middle of a much longer conversation that took place in Wang’s studio, located in the historic building of the former Federal Reserve Bank in DTLA.

MAGNUS EDENSVARD: During your undergraduate studies in Beijing, I believe you were on a more scientific academic trajectory?

ASTRA HUIMENG WANG: Yeah, my focus was in the field of implantable medical devices and spinal cord stimulators. But I was always trying to do something else in the meantime. I interned at a newspaper, and soon realized that that’s not really for me. I worked as a translator and interpreter and taught at some point as well. I traveled quite a bit when I was still in undergrad. Then I went on this long journey that took me to every continent except for North America.

ME: So these journeys were ways for you to seek out experiences that, to a large extent, you had only read about in books while growing up in Inner Mongolia?

AHW: Yes, and it’s how I learned the English language—largely through the lens of fiction. I was this coming-of-age avid reader who had a lot of trust in these novels, for better or worse. Proust wrote about how it was crucial for a simulacrum to find its way into the imagination first, before seeking out a counterpart in reality. If one of these authors had written about a specific place, I would find motivation to go and visit. So right after college, I visited Kars in Turkey almost entirely because of Pamuk’s Snow. There’s this hotel where they believed he stayed as he wrote the book. A translator later told Pamuk that everyone hated him in Kars, because the city seemed so harsh and hopeless in his book. [He] then allegedly confessed that he’d actually never been to the city. It seemed unlikely to me, but nevertheless intriguing—when reality confronts fiction in unexpected ways. It was also in that region where I met a German artist and writer who became a dear friend. We soon started traveling together, and we would talk about the lives we would go back to after our journey inevitably ended. One day she was like, Maybe you should apply for an MFA? I didn’t even know what that was at the time, or if I could apply with a bachelor’s in engineering from a university in China. I did a lot of googling and decided to apply. This was when my life path was altered, and I didn’t even know it at the time.

ME: You have your second solo show coming up in LA. Can you tell me a little more about what you are researching and what you will be showing?

AHW: Well, I’m very interested in the falling apart of a fantasy. It is an incredibly intriguing process. It causes disappointment. It causes wars and revolutions. So much of my research and my practice for the past couple of years has been rooted in this. If the very thing upon which you built your cultural identity falls apart, how do you rebuild it amongst the ruins, in the aftermath? How do you perceive reality in a new light? And how do you imagine a future separated from fiction? These are the questions I’ll ask and that my new work will attempt to explore.

GENEVIEVE GOFFMAN BY PAMELA BERKOVIC

Rendering of 'Two Monks Observing,' 2024 ny genevieve goffman

MODERN ART

Words: 913

Estimated reading time: 5M

By Magnus Edensvard

Genevieve Goffman (b. 1991, Washington D.C., US) is a New York-based artist whose work taps into the potential of 3D printing, bringing rich, speculative narratives to life by reimagining historical events with a fantastical twist. The Yale MFA graduate’s approach feels akin to the sci-fi hyperbole of Philip K. Dick’s storytelling, creating alternative realities and what-if scenarios that ask unexpected questions about history, memory, and the structures that shape our understanding of the past as well as the present.

Genevieve’s sculptures, crafted in pre-dyed vinyl, resin, and bronze, often take on the form of intricate, miniaturized worlds. Her works blend gothic architectural elements with a playful, stage-set quality reminiscent of Wes Anderson’s meticulous dollhouse aesthetic. There’s also a posthumous nod to the subversive spirit of Mike Kelley—each piece feels as if it exists within a reconstructed historical affair, where reality is twisted, reassembled, and given new life. Her cast of characters includes monks, house mice, and occasionally US patriarchs from the Civil War era, each caught in a world where history has turned topsy-turvy.

MAGNUS EDENSVARD: Genevieve, tell us about the origins of the Vineyard Sculpture you are currently working on.

GENEVIEVE GOFFMAN: Well, it all started with my brother. He’s obsessed with vineyards. When we travel together, he insists on touring them—comparing wines, learning about the process. I’m not that into it, but during one of these tours I discovered a tool that sparked something in me. It’s called a refractometer. You squish a grape inside it and it measures sweetness. That got me thinking about Geiger counters, which I collect, and how they measure something entirely different—radiation.

I started imagining a vineyard in the future where the earth is irradiated and grapes are radioactive. The more radioactive the grape, the more potent the wine. There was something poetic in that comparison.

ME: That’s such a striking juxtaposition. How did the narratives evolve from there?

GG: After that vineyard visit, I remembered reading about monks in France who’ve been making wine for hundreds of years in the same monastery. That led me to imagine this alternate history where a group of monks, isolated in the French mountains during WWII, are watching the world outside fall apart. They’re distanced from the violence, but they’re still aware of it. Instead of engaging, they keep making wine, and in my narrative, the wine becomes their way of recording history. It’s like their entire purpose shifts from religious devotion to winemaking as a method of documentation. So, this sculpture imagines wine as a kind of record of destruction. But, like all attempts at recording history, it’s imperfect—flawed. The monks aren’t actively involved in the chaos outside, yet their wine still attempts to capture it, almost like a timepiece. But the time it records is muddled, impossible to pin down.

ME: Can you describe a little more your thinking for the formal aspects of this new piece?

GG: It’s a wall-hanging sculpture that mimics the form of a clock, but one that doesn’t work. The dial is turnable, and it shows different phases of grape harvesting—some real, some I made up—but none of it lines up. The whole piece is framed by vines that weave through the structure. The vines symbolize how the monastery’s purpose has been overtaken by winemaking. In the center of the piece is the figure of a monk, looking out at the world, but all he sees are these vines and a system of record-keeping that is doomed to fail.

ME: There are themes running through your work amounting to some sense of disruption and failure. How do such ideas factor into the Vineyard Sculpture?

GG: The idea of failure is essential to this piece. I’m drawn to how we try to measure, record, and make sense of things like time and history, and how often those systems fall apart. It’s about how history is often imperfectly remembered. We think we can record events with accuracy, but we can’t. It’s always fragmented, incomplete. There’s something almost funny about that—setting up these grand systems, only for them to crumble under the weight of their own ambition.

ME: This piece feels like part of a larger narrative. Is it connected to any other future works?

GG: It’s the first in a series of three. The story is still unfolding. I can’t wait to see how people engage with this idea of a failed timepiece—a clock that doesn’t tell time, and a wine that records nothing.

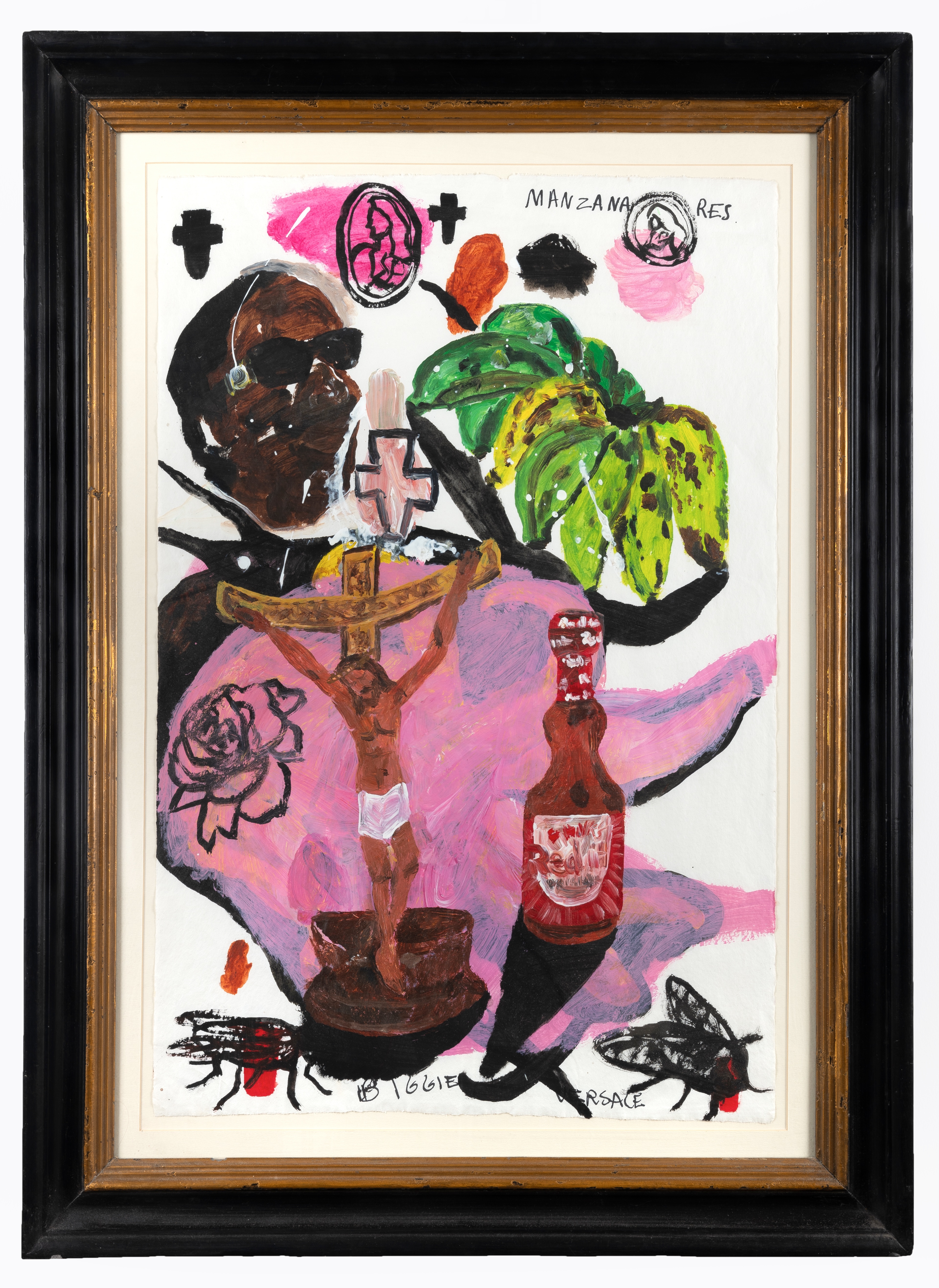

MAÏA RÉGIS BY RICHARD BUSH

'Biggie Versace and the Christ'

84 x 62 cm with frame

Photography by Fausto Brigantino

Courtesy of maïA RÉGIS AND Francesco Pantaleone Palermo/Milan

MODERN ART

Words: 762

Estimated reading time: 4M

By Magnus Edensvard

Maïa Régis (b. 1995, Paris, France) graduated from the Royal College of Art, London, in the fall of 2019 with a master’s degree in painting. Yet even before that time, she had been working nomadically, doing various residencies and setting up temporary studios in places like Paris, London, and the island of Pantelleria, though she always retained Palermo as her main outpost.

Working across different mediums comes naturally to Régis. When I caught up with her at her studio, she had just returned from London where she had presented a hand-painted design for a limited-edition sneaker commissioned by Golden Goose. The project had been part of a Women In Art event held at the Royal Academy the evening before, where all commissions contributed towards raising funds for the Make-A-Wish Foundation. Next up for Maïa is her first solo show in her adopted hometown of Palermo, at the eponymous Francesco Pantaleone Gallery, located just a few blocks away from her studio.

MAGNUS EDENSVARD: What are you working on at the moment, Maïa? Looks like a lot of portraits there in the background?

MAÏA REGIS: I’m going over all these series on paper that I did, mostly portraits I’ve painted over the years. They’re people I’ve met or people I’ve seen taken by different photographers who inspire me. I guess I paint them when I find their faces have something particular or “paintable,” with a lot of expression and character. It could be a celebrity, but it could also be someone super random on the street that I don’t know. If they have a face that I feel like painting, I just paint it.

ME: Are you currently selecting some of these works for your next show?

MR: Yes, it’s going to be a work-on-paper show including mostly painted portraits. Some of them will be pinned, but I’m also going to include some works that I’ve personally framed. They’re frames that I bought at Palermo flea markets, traditional Baroque golden or black Sicilian antiques. Sometimes they act as an extension to the character’s identity that I’ve portrayed, and the frames become part of the work. I love the contrast between more abstract works and the frames makes them a lot more present, almost formal.

ME: Remind me, what’s the show title? And what other themes are you researching for this as you prepare?

MR: The show title is Mosche e Cristi—meaning Flies and Christs in Italian—and to me, this springs from the poetics of the South, Sicily in particular, where the holy goes along with more somber aspects of life. It’s the popular devotion that I find particularly moving, especially in the very poor neighborhoods of Palermo where I live and have my studio, in Ballarò and Albergheria. On one side, there’s crime and poverty, and on the other side, there’s a theatrical aspect of life in these streets. Families and neighborhoods often organize religious processions with the local church, during which people carry the load of a saint on their shoulders to repent, while bands follow them playing drums and trumpets.

ME: Your work references this very personal and specific milieu—from the street markets, the churches, and the Palermo architecture, to the frequent processions through the streets. Can you tell me about your history with the city, and how that’s being explored in this new body of work?

MR: I’ve been working here for a long time now. At the moment, my studio is in this house that had been abandoned for over 40 years—all decaying, but it’s a beautiful palazzo with very high ceilings. My previous studio was in Vucciria, a well-known market in the center of the city. You could hear people yelling and the smells of street food would come in through the windows while I was working; you were completely immersed. This environment is very naturally an inspiration to me.

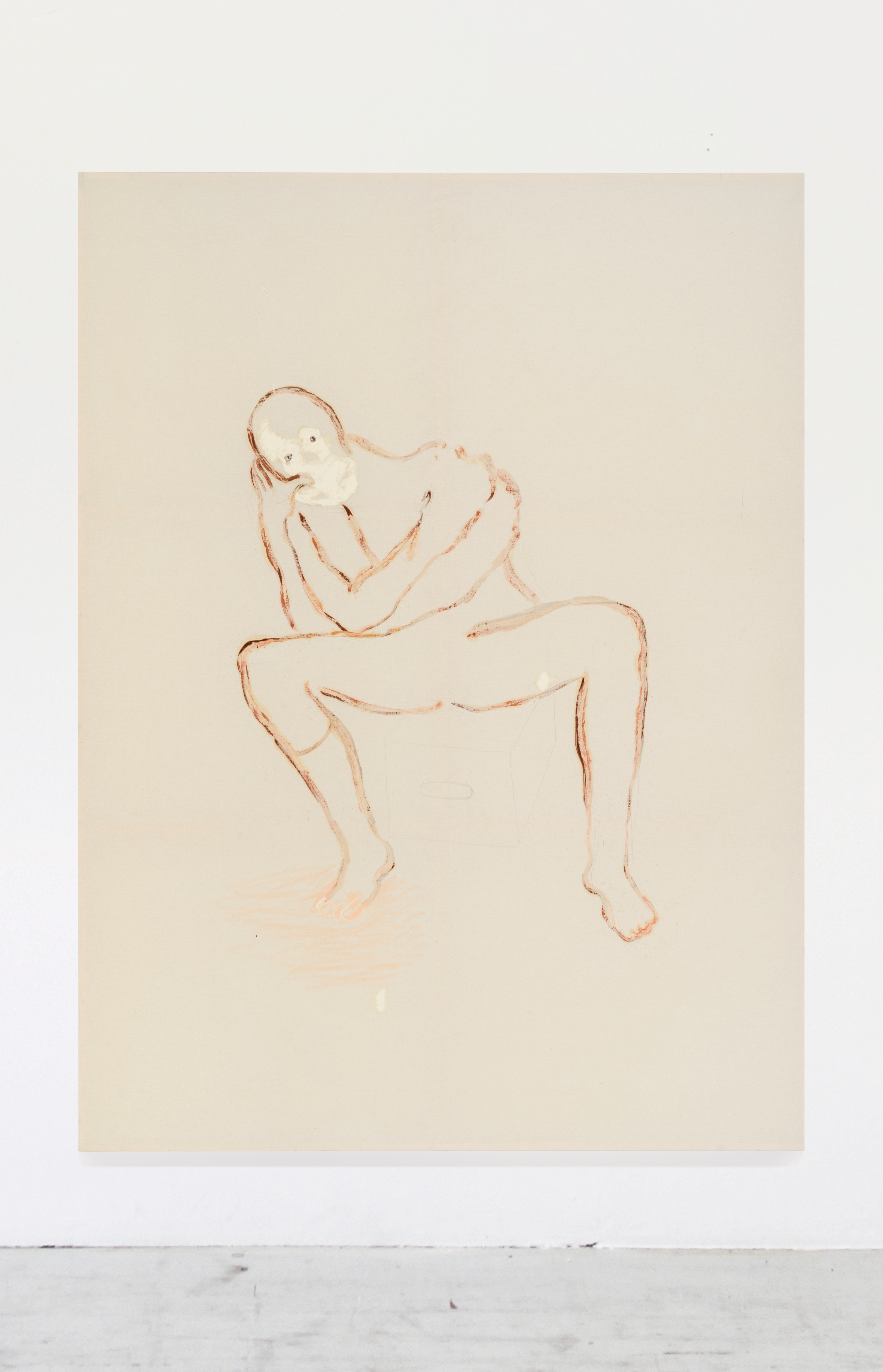

TOLIA ASTAKHISHVILI BY ELIOT LEBLANC-HARTMANN

'Hesh,' 2016

Canvas, oil, 253 cm x 190 cm

Courtesy of TOLIA ASTAKHISHVILI AND LC Queisser Gallery

MODERN ART

Words: 989

Estimated reading time: 5M

By Magnus Edensvard

Tolia Astakhishvili (b. 1974, Tbilisi, Georgia) works and lives between Berlin and Tbilisi. Over the past two decades, she has steadily carved out a practice that is as sensitive in its approach as it is monumental in scale. Her work often unfolds like an investigative journey, akin to a geologist meticulously uncovering layers of meaning. By examining the history and original uses of the spaces she inhabits, along with traces of their previous dwellers, the artist’s installations take on a commanding presence as she prescribes acupuncture if not an entire rehaul of the preexisting architecture. Her process frequently involves inviting collaborators, artists, curators, and family members into her conceptual framework, allowing the space itself to become a living, evolving narrative.

Having just participated in an exhibition at MACRO titled Post Scriptum. A museum forgotten by heart, Tolia talked a little about her upcoming trajectory—a solo show at LC Queisser, Tbilisi, followed by a group show at MoMA PS1 in New York—whilst also referring back to her recent groundbreaking exhibition between father and mother at SculptureCenter New York this year. These exhibitions, interconnected by both personal and spatial explorations, form the basis of the conversation that follows.

MAGNUS EDENSVARD: I’d love to hear more about your next projects.

TOLIA ASTAKHISHVILI: Right now, I’m focused on a few things. In November, I’ll be working on a solo show at the gallery LC Queisser in Georgia. It’s a space I’ve shown work in before, but this will be my first solo exhibition there. My plan for this show is different from what I’ve done in the past—my initial idea was to focus more on painting, but somehow the spatial aspect always takes over. Space is really important to me, and it becomes a part of the work itself. For this show, I’ve prepared canvases that cover the walls entirely in a segmented puzzle-like fashion, almost repeating the architecture. Even though I wanted it to be more about painting, it’s turning into something more installation-based, as always.

ME: What are the underlying themes and references for your show at LC Queisser?

TA: I’m interested in the idea of fragmentation—how each part becomes its own universe. I’m experimenting with how these pieces come together through the process of creating the installation. It’s a bit more experimental, more risk-taking, than what I’ve done before.

ME: Will this show include collaborations or is it a solo effort?

TA: It’s a solo show, but I’m including my mother’s work. She’s also an artist but has never exhibited before because she’s always felt it wasn’t “perfect enough.” I’ve been encouraging her for a while, and now she’s agreed to let me include a few of her pieces. I took some of her small works, framed them, and will be presenting them in a very classical way. It’s a way for her to see her work in a different context, and I’m curious to see what will come of it.

ME: That’s fascinating—it almost reverses the traditional parent-child dynamic. How are you approaching this curatorial role with your mother’s work?

TA: It’s definitely a shift, especially since she’s always been so critical of her own work. So I’ve taken the initiative and will present the works the way I think they should be shown. It’s an experiment for both of us—seeing her work through my perspective, while still giving her the freedom to change things later if she wants.

ME: You’ve mentioned a more experimental approach for your upcoming show. Is that a path you plan to continue for your other projects?

TA: Yes, I’ve been trying to embrace more process-based work lately, planning less and making more. I’m also doing a show at MoMA PS1, where I’ll be working with some materials left over from my previous installation at SculptureCenter. There’s one element from that show, a long chute that people could stand underneath and look up through. I’m planning to transform it into a horizontal tunnel on the floor. It’s a work in progress.

ME: You’ve shown your work internationally, and now you’re returning to New York for another exhibition. How has that shaped your practice?

TV: It’s been great, especially getting to work more deeply with spaces like SculptureCenter and PS1. I joke with the team at PS1 that I now have my own personal storage space there because of all the materials left from the first show. It feels like each exhibition builds on the previous one, creating this ongoing relationship with both the space and the city.

ME: How do you balance planning versus spontaneity in your work?

TA: I’ve had periods of intense planning, where I’d meticulously execute my ideas. But now, I’m more interested in spontaneity—letting the process unfold naturally. It feels like each stage of my work is a different life. Right now, I’m in a phase where I want to embrace the unknown and let the work evolve as I go along.

TORI WRÅNES BY TERJE ABUSDAL

'Multistand' BY TORI WRÅNES (performance as part of 'Dastic Pantsat' Carl Freedman Gallery, 2014)

Photography BY Alice Slyngstad

MODERN ART

Words: 1126

Estimated reading time: 6M

By Magnus Edensvard

Tori Wrånes (b. 1978, Kristiansand, Norway) is a transdisciplinary artist who blends sound, performance, sculpture, and installation to create immersive, dreamlike experiences. Her work dissolves boundaries between fantasy and reality, inviting audiences into surreal worlds where characters and choreographed performances take on a life of their own.

We reconnected from her native Oslo, where Tori is preparing for the 2025 Festival Show at Bergen Kunsthall. This prestigious museum will host a major exhibition next spring, for which Tori intends to transform the space into a giant seafaring vessel, or so she whispered, as if confiding just a small part of a much longer story.

We began our conversation by looking back at Tori’s early experience as a lead vocalist in a rock band, and how that influenced her unique approach to becoming the performance artist she is today. She discussed how sound becomes a physical presence as it interacts acoustically with space and architecture, as well as how her performances have been staged in remarkably diverse environments—from hanging from the top of a crane over the harbor of Oslo to underwater worlds off the coast of Thailand—often incorporating elements beyond her control, resulting in spontaneous and transformative moments.

By pushing against constraints and challenging the normative values under which many of us live, our conversation was continually fueled by Tori’s palpable optimism and gratitude for being able to practice and perform her ideas as an artist in today’s deeply fraught and challenging times.

MAGNUS EDENSVARD: How did your experience as a musician in a touring rock band evolve into what you’re doing now as a performance artist?

TORI WRÅNES: It was a huge part of my development. The voice was always my main instrument, and that shaped how I think about sound and performance today. When I started at the Art Academy, I found freedom in improvising performances. It all began by accident one evening when I threw a gigantic scarf around my head and started singing wildly on stage. I had somehow found a way to express something raw and unfiltered. Later, when I started to add more masks and blindfolds, I realized I could go even deeper. These elements allowed me to distance myself from my own image, which was strangely freeing. I could connect with the audience on a different level, beyond the limitations of my own physical presence.

ME: That’s fascinating—this idea of creating a different self and sense of self at the same time, through performance. Your work seems to take place in surreal, dreamlike, and often absurd settings. Has this freedom, to create new identities through performance art, helped you inhabit these worlds?

TW: Definitely. It’s like entering another realm, a dreamlike space that feels more honest than the everyday world. In these performances, I can create characters that aren’t bound by the usual rules—whether they’re trolls, sea creatures, or some other fantastical being. It’s an adventure into a different space that exists outside societal norms. What I find most interesting is how this transformation affects the audience. There’s something magical that happens as people engage in a way that allows the experience to take on a life of its own, sometimes way beyond my control.

ME: Speaking of unusual spaces, you’ve performed in some incredible environments, like underwater and in forests. What’s it like using your voice in these different elements, and how do they affect your performances?

TW: I see sound as something physical, something you can almost touch. Each environment has its own texture that interacts with sound in unique ways. For example, when I put down the cornerstone for the new National Museum in Oslo, I was lifted into the air by a crane while singing. My voice sketched the architecture of the museum to come, as the clock tower chimed. When I landed on the ground, all the boats in the harbor began sounding their horns. I wanted the museum to shake hands with its new neighbor in a humble way. In Bolzano, Italy, I had musicians and the audience in a chairlift, and suddenly cowbells worn by a herd of grass-grazing cows below started to clang. It felt like the environment itself was responding to my performance. Another example is performing underwater in the winter. The sound changes completely when you’re submerged—it disappears or becomes something entirely different. The audience was watching from a platform on the surface of the sea, looking down into the water with binoculars. We weren’t connected by the same sounds, which created this strange brain trick. I even installed a light chamber underwater to illuminate the seabed. At one point, the Northern Lights appeared in the sky over the sea, and it synced with the lights I had set up beneath the water. It was magical and again, strange coincidences that no one predicted started to play out.

ME: You call on fantasy to support many of your works. Do your performances offer an escape for both you and your audience?

TW: In society, everything has to fit into boxes, like age, gender, profession. But in the world of performances, those categorizations don’t hold up. My characters aren’t bound by those labels. They exist in a space where they can just be as well as grow, without explanation or justification. But it’s also about personal expression. Creating these creatures allows me to explore parts of myself that might not come out in everyday life. It’s freeing to create a world where those restrictions don’t apply, and I think we all need that, especially now.

Art Editor-at-Large

Magnus Edensvard

Talent

Astra Huimeng Wang, Genevieve Goffman, MAÏA RÉGIS, TOLIA ASTAKHISHVIL, TORI WRÅNES

PRODUCERS

SYD WALKER, IAN CRANE

Beyond Noise 2026

Art Editor-at-Large

Magnus Edensvard

Talent

Astra Huimeng Wang, Genevieve Goffman, MAÏA RÉGIS, TOLIA ASTAKHISHVIL, TORI WRÅNES

PRODUCERS

SYD WALKER, IAN CRANE

Beyond Noise 2026