Noise

ISSUE NO. 03: LITA ALBUQUERQUE

BETWEEN THE LINES

Words: 2450

Estimated reading time: 14M

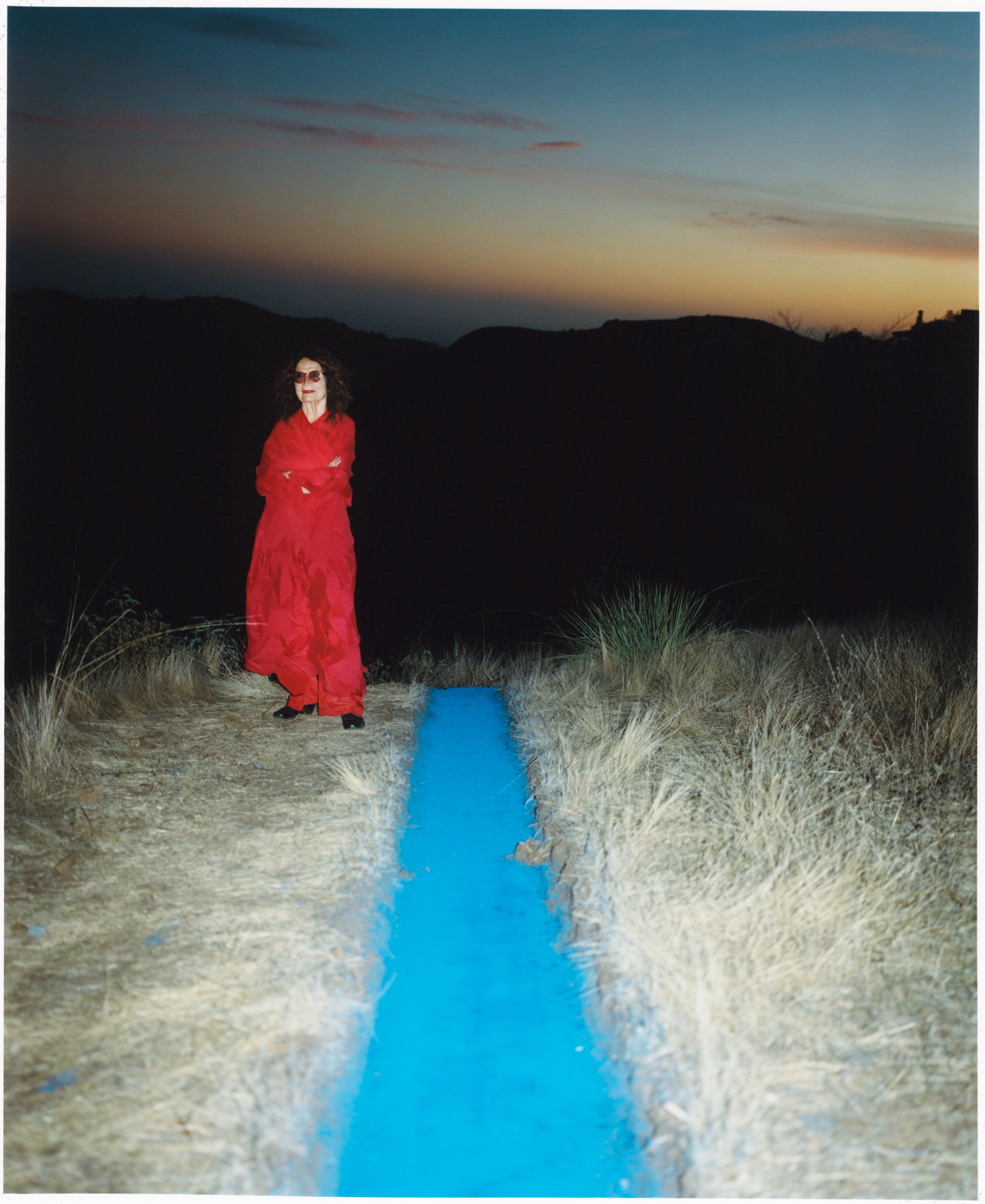

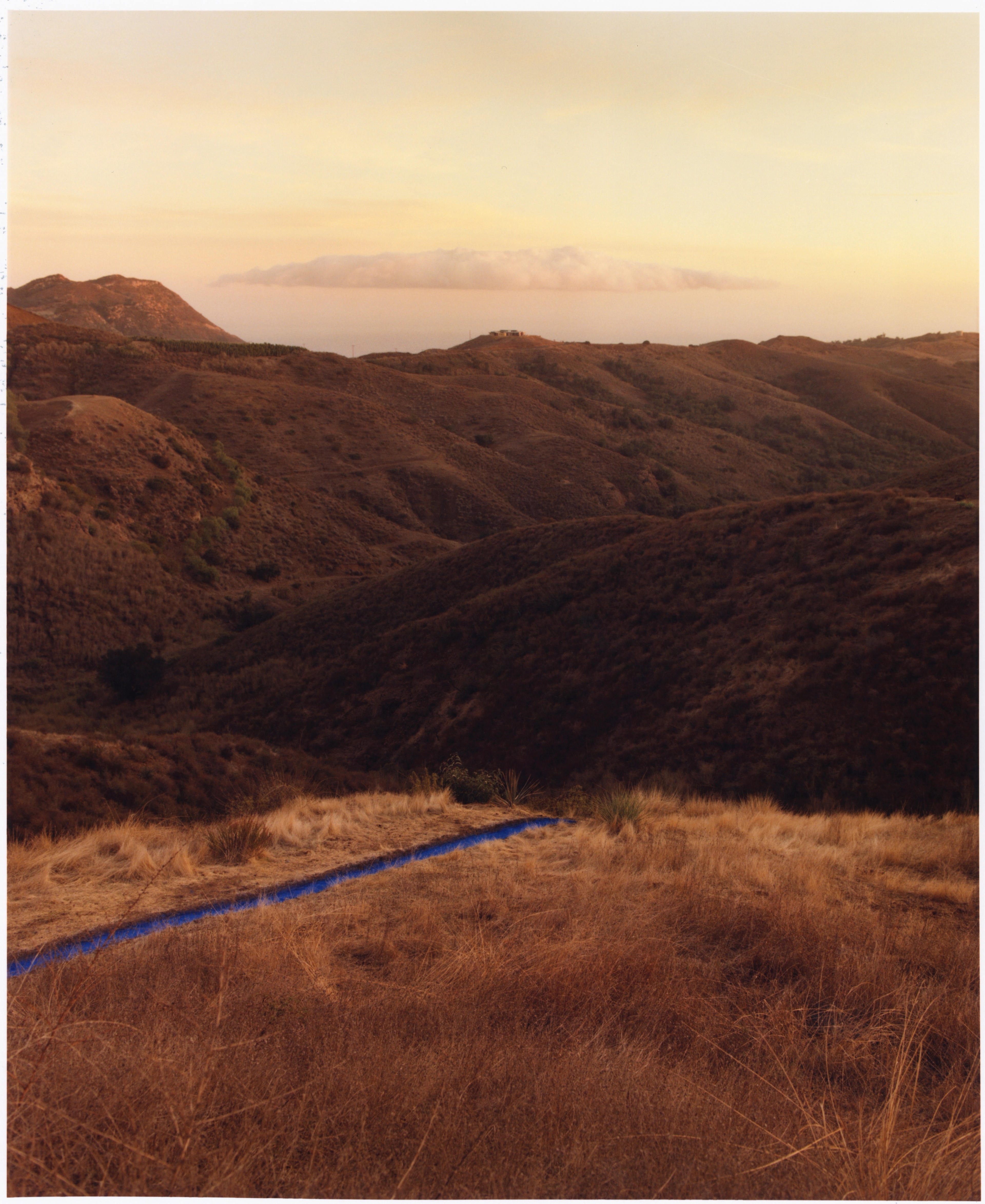

LITA ALBUQUERQUE USES THE EARTH AS HER CANVAS, CONNECTING DISPARATE LANDSCAPES WITH PIGMENT AND LIGHT.

By Magnus Edensvard

In late January 2025, as the raging Los Angeles wildfires began to subside, I set off to visit Lita Albuquerque at her Malibu studio and home. My aim was to check in and provide space for her to reflect on nearly five decades of an exploratory art practice, and how she had sustained herself through the past weeks—weeks in which her city burned and America, as lauded by its newly inaugurated president, was supposedly on the brink of becoming great again. Additionally, I was eager to see the newly installed Malibu Line in situ and learn more about its origins and forthcoming manifestations.

At the time, much of the landscape between LA and Malibu had been transformed into a wasteland of debris and scorched earth, resembling a war zone. With the more scenic Pacific Coast Highway closed due to fire damage, my dog Lulu and I were rerouted inland, taking the 101 freeway until we reached the turnoff onto winding highland roads. We finally arrived at the top of the canyon, where her newly rebuilt home stood.

As we were greeted, we were once again reminded of the warmth and wisdom that Lita exudes. Her Malibu Canyon compound that she designed every part of is a testament to her enduring commitment to the arts, her deep engagement with the landscapes we inhabit, and her ability to create aesthetic connections between the psyche, the environment, and the cosmos above.

Just the night before, Lita had been honored at a gala at the Palm Springs Art Museum, where she will present a major survey exhibition next year. Prior to this, her work has been exhibited at some of the world’s most prestigious institutions, including a career survey at the Santa Monica Museum of Art, the USC Fisher Museum of Art, the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C., the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris, among many others. Her influence also extends into academia, with a longstanding and revered tenure as a professor at the Graduate Fine Art Program at the ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena.

Lita’s home and studio, perched high in the hills, offered breathtaking views that set the tone for our conversation. As we spoke for several hours, the day gradually gave way to a spectacular sunset, casting a glow over the landscape—one that felt like a conducive backdrop to the conversation that followed.

MAGNUS EDENSVARD: This is truly a unique property, with the most expansive views. How did you first come across it

LITA ALBUQUERQUE: Interestingly enough, this was a property that my husband and I—together, we have four kids—moved into in 1990. It was amazing, super funky. It really became a center of creativity for all my children, who also have these amazing friends. There were dance performances, film screenings constantly, and weddings that were outrageous, that kind of thing. Very fertile. So it’s really got a lot of energy.

ME: Yes, it does feel like that kind of home. Today, we see a newly-built property that feels a bit like one of your sculpture installations. Tell me what’s been happening here of late.

LA: Well, in 2018, the Woolsey Fire came and destroyed everything, including the studio that was here. It’s been six years since we started rebuilding and we’re still not done. The first time my daughter Isabelle—who had at this point moved out—came back after the fires, she went, This is great! It’s like being on an island! As you can see, we now have these 180-degree views. We had to cut down 42 trees that were so badly burned. It’s a new landscape for a completely new chapter.

ME: Has the rebuild since the last LA fires remained a conversation between yourself, your children, and your husband?

LA: Not as much [as before], because it took so long to get permits. That’s why Malibu Line turned out to be an interesting, healing thing, in that it was the first time I spent many days alone on the property since the fires. I’m from North Africa and I really wanted to recall the feeling of that landscape.

ME: I read about your childhood between France and Tunisia. The landscapes you describe, the soil and the light and everything—it feels like these memories have become important elements in this new chapter.

LA: Yes, they are—that relationship to the land. There was another property that burned down in 1997 near Tuna Canyon. That’s where I really grew up as an artist, because it’s close to the ocean. That’s where the Malibu Line first began to be drawn. You could see the sun going from east to west, and the moon. I’d already been sensitized to the land, because of being in North Africa. It is palpable. It’s like an entity. I think history plays an important role in the earth, color, and, of course, cultures. Malibu Line revisited had to do with a longing for Tunisia. We are going to do another Line in Tunisia, in Sidi Bou Said, where I grew up. It was founded by a Sufi in the 11th century. French artists, French philosophers, Matisse—a lot of people went there. It’s on a promontory, and it’s all white and blue. I was raised in the Catholic convent next to Sidi Bou Said. So all these confluences of how I think about the universe, about human life on the planet, were instilled in me from a very early age.

To your point, the soil influences many things about our decisions we often are not conscious of. Living in these landscapes, and also in between these cultures and religions, with both Sufi and Catholic influences, must have been a pretty intense download at such a young age.

I didn’t think of it that way. There are many levels to it. Being so young, doing mass at five in the morning while hearing the calls to prayer from the mosque twice a day—I just took it in stride. At that time, it was a French prefecture, so I thought of myself as a French girl. My mother’s side of the family had been in Tunisia forever. To this day, I’m still trying to figure it out.

ME: Have you found a site for this ongoing exploration?

LA: I have. It’s right next door to the convent I went to as a young girl. This convent is located across a hill that has the same relationship to the Mediterranean as Malibu Line has to the Pacific Ocean. The idea is that it is set in one direction, and Tunisia Line goes in another. It’s the idea of meeting. I had an image in my mind of the planet from space, where you see these blue lines aligning, and this fantasy of this one-eyed, giant cosmic being picking up this little sphere and going, I wonder what this is.

ME: I like the notion of an outer space perspective. You’d be able to see the two Albuquerque lines along with the Great Wall of China.

LA: [Laughs] Well, whether or not we’ll be able to use it, we’re working on that now. The curator, Ikram Lakhdar, is trying to get communication going. You see, the president’s police station has moved into the old convent.

ME: It seems like you’re taking everything in your playbook and bringing it together as a legacy, but in a very playful way.

LA: We’ll see what happens. With Malibu Line I wasn’t going to do it here. The idea was to reproduce it on the same property as the artist colony I lived on. Unfortunately, someone took it over and changed all the locks. The owners won’t do anything about it. We tried to do it in a few parks, and that didn’t work out. Then, one day, I thought, Why not do it here? I never considered it [before] because it was so far from the ocean. But then I started looking, and I found a spot that didn’t have the same geometry.

ME: If I’m not mistaken, this is a project that you have brought back into the fold?

LA: Yes, since 1978. The [original] Malibu Line was the first outdoor project I did. That came out of Robert Irwin. I was quite green in terms of what art was, and it was the first time I really saw that art was about space. I was taking dance at the time, and I was very aware of the verticality of my body. One day, I was taking a hike by myself. I looked at the horizon line and realized that my body and the horizon formed a cross. I wondered if that’s how symbols are formed, through the interrelationship of a human being and the environment. So I thought, I’m gonna do a perceptual cross. What I ended up doing was very simple: 14 inches by 41 feet. Very shallow. There was some kind of gravel underneath, and I filled it with blue pigment. So perceptually, the blue of the line went all the way to the horizon to form a cross. It was really an incredible moment.

I did two other pieces on that property. I had a blue circle where the moon set. I had been to Death Valley and wanted to cover the entire mountain range. My friend said, “They’re not going to let you do that.” So I didn’t do a mountain range—I did a boulder. It was minimal art. An abstract gesture, but a symbol. It was something that I saw as a work of art. It was just this need to connect; like the circle was connecting to the setting moon, the blue rock was connecting to the sky. Compulsion, I guess I could call it. I was very obsessed. People who lived in the artist colony thought I was totally nuts.

ME: How did dance influence this experience of finding the horizon in that way?

LA: I had wanted to be a dancer. It was just really noting my own geometry, that line against that line. I’m very interested in movement and alignments.

ME: Going back to Tunisia, when you mentioned the Sufis—they are connecting to the spirit world through movement. You also mentioned how your body and the soil on which you dance, walk, or stand upon are all in some mysterious communication. Are you teasing works out into manifestations through these different experiences, and if so, at what point did you first decide to bring the line back?

LA: I had an incredible experience in 2017. I went to Wyoming with some friends to see the Great American Eclipse, and we were all lying down on the road by ourselves. And a young guy said, “At totality, take off your glasses.” The black obscures the sun, except for the sunburst outside it. I could feel the light as if I could pick it up. But as I was staring at it, I saw the orb of the moon, and I saw the distance between the moon and the blocked-out sun. Therefore, the Earth was also an orb in space. I experienced visually that we’re in space, and this is something I’ve always put into the work. If the Earth is a sculpture in space, then the cosmos is an installation in which we partake every day. Shortly after this experience, I was working with Ikram, and I showed her the property. She knew quite a bit about the work. She said, “It seems that it’s a piece about longing. What do you think about restaging it?” And I said, “I’ll do it if we can have a sister piece in Tunisia.” I think of the Earth as a sculpture in space.

ME: You said you had a couple of turning points, where you just happened to be in a place at a certain time, and you have moments when you receive information.

LA: Well yes. You see, when I imagine observing Earth from space, it has nothing on it. No continents, nothing but gold-tip pyramids, all aligned to the stars. Stars are completely surrounding us in space. There’s evidence that we had such mapping—remnants all over the world. And I thought, I’ve got to do something. Obviously, I’m not going to do pyramids, but maybe I can do points of stars. I was on an airplane, and the idea of starting at the north and south poles came to me. I ended up working with the National Science Foundation and doing this large piece. I brought 99 blue orbs—different diameters corresponding to the stars above—and worked with an astronomer. We did this amazing reverse sky on the ice. If you’re imagining two stars here, two stars there, with the rotation of the earth, you get what resembles the double spiral of the DNA.

ME: Do you find the less the desire to find the ultimate answer is, the more mysterious the search for an answer becomes?

LA: Absolutely. Robert Irwin [said] that art is inquiry. And so the image I had was like a plow, and what falls is the art. But the trajectory is what motivates, not always what comes out of the inquiry. I think if we had answers to everything, we would be very bored.

PHOTOGRAPHY

COLE BARASH

Beyond Noise 2026

PHOTOGRAPHY

COLE BARASH

Beyond Noise 2026